Most Americans cannot explain how their health insurance works. This is not because they are unintelligent. It is because the system was designed by economists, not patients.

Three mechanisms control what you pay when you get sick: the deductible, coinsurance, and the out-of-pocket maximum. They sound like consumer protections. Their origins tell a different story.

How the three mechanisms work

The deductible is the amount you pay before your insurance covers anything. If your plan has a $2,000 deductible, you pay the first $2,000 yourself. Your plan does not contribute a dollar until you cross that line. Preventive care is exempt under federal law, but everything else counts: the urgent care visit for a sinus infection, the blood work your doctor ordered, the X-ray after you twisted your ankle.

Coinsurance kicks in after you meet your deductible. It is a percentage split. A typical arrangement is 80/20: the plan pays 80%, you pay 20%. An MRI that costs $1,200 means you owe $240.

The out-of-pocket maximum is the ceiling on what you pay in a plan year. Once your deductible and coinsurance payments add up to this number, the plan covers 100%. The federal cap for 2025 is $9,200 for an individual. For 2026, it rises to $10,600.

These three mechanisms stack in sequence. To understand what that feels like, consider two people on different plans facing the same year.

Sarah and James both break an arm

Sarah is on a typical PPO: $2,000 deductible, 80/20 coinsurance, $6,500 out-of-pocket max. James is on a high-deductible plan (HDHP): $3,500 deductible, 80/20 coinsurance, $7,500 out-of-pocket max.

In March, both slip on ice and break an arm. The ER visit, X-ray, cast, and follow-ups total $4,500.

Sarah pays $2,000 (deductible) plus 20% of the remaining $2,500 ($500 in coinsurance). Total: $2,500. James pays $3,500 (deductible) plus 20% of the remaining $1,000 ($200). Total: $3,700.

Neither has hit their out-of-pocket max. Both still have exposure for the rest of the year.

In September, both need outpatient knee surgery. Negotiated rate: $15,000. Sarah owes 20% coinsurance ($3,000), bringing her year-to-date total to $5,500. James owes the same $3,000, bringing his to $6,700. The out-of-pocket max has not kicked in for either of them, and the median American household has less than $5,000 in savings.

Now consider David. Same HDHP as James. He has a persistent cough in January. The doctor visit would cost $250. He has not met any of his $3,500 deductible. He decides to wait it out.

The cough was early-stage pneumonia. By February, David is in the emergency room. The bill is $8,000.

David's plan worked exactly as designed. It made him hesitate to get the early care he needed.

A system designed against you

These mechanisms were not born from medical evidence. They were borrowed from car insurance.

In 1949, Liberty Mutual created the first "major medical" health insurance policy for a group of General Electric engineers. It had a $300 deductible and 25% coinsurance, modeled directly on automobile collision coverage. The logic: a deductible discourages frivolous claims. By 1961, 34 million Americans were enrolled in plans built this way.

The intellectual justification arrived through three economics papers in the 1960s and 1970s. Kenneth Arrow identified moral hazard: when someone else pays, patients consume more. Mark Pauly argued this overconsumption was rational, and that full coverage was therefore economically suboptimal. Martin Feldstein claimed that raising coinsurance rates would save billions. Together they built a framework that treats healthcare like any other commodity. Give patients skin in the game and they will consume only what they truly need.

The federal government spent $295 million (in today's dollars) testing this theory. The RAND Health Insurance Experiment ran from 1974 to 1982, randomly assigning over 7,700 people to plans with varying cost-sharing. The headline finding: people on free plans spent 45% more than those paying 95% coinsurance.

The finding underneath the headline was devastating.

Cost-sharing reduced appropriate and inappropriate care in equal proportions. Patients did not become smarter consumers. They did not learn to distinguish a necessary visit from an unnecessary one. They went to the doctor less. Period.

For the poorest and sickest 6%, free care produced meaningfully better outcomes: lower blood pressure, better vision, an estimated 10% reduction in mortality for hypertensive low-income patients.

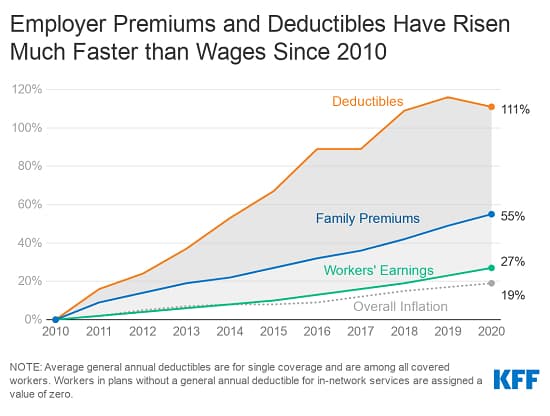

Every major study since has confirmed this pattern. A 2017 study found that switching employees to a high-deductible plan reduced spending 12 to 14%, entirely through people using less care. Zero evidence of price shopping. Even after two years. Consumers did not learn to find cheaper providers. They learned to avoid providers entirely.

The most damning evidence concerns primary care. High-deductible plans reduce preventive visits even though federal law makes them free. Nearly 20% of HDHP enrollees do not know their preventive care costs nothing. One study found that while HDHP enrollees initially had fewer doctor visits, their hospital admissions doubled three years later.

Doubling copayments for diabetes medications reduced adherence by 23%. For blood pressure medications, 10%. These are not optional treatments. These are drugs that prevent heart attacks.

The economist John Nyman put it simply: conventional moral hazard theory misunderstands why people buy insurance. People do not just buy risk protection. They buy access to care they could not otherwise afford. Much of what the industry calls "overutilization" is patients getting care that improves their health.

Seven decades of evidence point to one conclusion. Cost-sharing at the point of primary and urgent care does not make patients smarter consumers. It makes them sicker.

Why Rivendell plans are different

We designed Rivendell around one principle: the moment a member needs care should never be the moment they face a financial decision.

Every Rivendell plan has a zero-dollar deductible. Primary care is free. Urgent care is free.

This is not generosity. It is plan design that follows the evidence instead of ignoring it.

When you put a price on a doctor visit, people skip it. The ones who skip are disproportionately the sickest, lowest-income, and least able to absorb a surprise bill. The $250 they saved becomes the $8,000 ER visit. The skipped blood pressure check becomes the hospitalization.

Primary care and urgent care are where problems are small and cheap to solve. Every dollar of friction at that level generates multiples in downstream cost. Removing that friction is not just better for members. It is better economics.

The insurance industry built cost-sharing to solve a theoretical problem called moral hazard.

We built Rivendell to solve the actual problem: people who need care and do not get it.