When I was shopping for health insurance for my startup Commonbase in New York, I assumed the process would be straightforward. We were a small team, young, healthy, no pre-existing conditions. The kind of group any insurer should want.

I was wrong.

The pricing came back at nearly $1,300 per person per month for a decent plan. For a team of 10, that's over $150,000 annually before any other employee benefits. Meanwhile, I knew founders at larger companies paying 20-30% less for equivalent coverage. Same city. Same network. Same benefits.

What I discovered was a regulatory architecture that systematically forces small businesses to subsidize a broken system, while large corporations opt out entirely.

How the Small Group Market Actually Works

If you have fewer than 100 employees in most states (50 in some), you're in the "small group market." This market operates under strict rules established by the Affordable Care Act:

Community Rating: Insurers cannot charge you more based on your team's health status. Sounds fair, until you realize it means your healthy 26-year-olds are priced identically to a group with chronic conditions.

Guaranteed Issue: Insurers must accept all small groups. Again, sounds good, but it means the risk pool includes everyone who couldn't get coverage elsewhere.

Mandated Benefits: Your plan must cover a comprehensive set of "Essential Health Benefits," plus whatever your state mandates on top. In New York, that's a long list.

The result? You're not buying insurance for your team. You're buying a share of the entire small group risk pool in your state. And in states like New York, that pool is expensive and shrinking.

New York's "Pure Community Rating" Problem

New York goes further than federal requirements. While the ACA allows insurers to charge older employees up to 3x more than younger ones (reflecting actual actuarial risk), New York prohibits any age rating at all. A 25-year-old engineer pays the same rate as a 64-year-old.

This is called "pure community rating," and New York adopted it in 1992—two decades before the ACA. The policy goal is social solidarity: everyone shares the burden equally.

The practical result is that young, healthy startups massively overpay relative to their actual risk, while older, sicker groups get a discount. Your Series A is subsidizing someone else's COBRA.

The ICHRA Option: Better, But Not the Solution

When founders complain about group plan costs, someone inevitably suggests ICHRA—Individual Coverage Health Reimbursement Arrangements. The pitch: give employees a tax-free allowance, let them buy their own plans on the individual market, and avoid the small group market entirely.

ICHRA has real advantages:

- Predictable employer costs

- Employee choice and portability

- Works well for distributed teams across multiple states

But ICHRA has a fundamental limitation: you're just shifting to a different broken market.

The individual market (healthcare.gov or state exchanges) uses the same community rating principles as the small group market. Your employees aren't escaping the risk pool, they're joining a different one, often with similar pricing problems and narrower networks.

ICHRA solves the administrative headache of multi-state coverage. It doesn't solve the cost problem. In New York, individual market premiums are just as inflated as small group rates. You're rearranging deck chairs.

Level Funding: The Alternative You're Not Allowed to Use

Here's what larger companies do instead: they self-insure.

A self-insured (or "self-funded") plan works differently. Instead of paying premiums to an insurance carrier who assumes all risk, the employer pays claims directly from their own funds. The company bears the risk, but also captures the savings when claims are low.

For a Fortune 500 company with 50,000 employees, this makes obvious sense. The law of large numbers means claims are predictable, and they have the cash reserves to handle volatility.

But what about a 30-person startup? That's where level-funded plans come in.

How Level Funding Works

A level-funded plan is a hybrid structure designed to make self-insurance accessible to smaller employers:

- Claims Fund: You pay into an account that covers expected medical claims, based on your specific group's health profile (yes, underwriting).

- Stop-Loss Insurance: You buy a policy that caps your downside. If any individual has claims above $20,000 (the "specific attachment point"), the stop-loss carrier pays. If total group claims exceed 125% of expected, the "aggregate" stop-loss kicks in.

- Administrative Fees: A third-party administrator handles claims processing, network access, and compliance.

The "level" part: you pay a fixed monthly amount, just like a fully-insured premium. But here's the key difference—if claims come in lower than expected, you get a refund. In a traditional plan, the insurer keeps that as profit.

Why Level Funding Saves Money

The savings come from two sources:

Underwriting: Unlike community-rated plans, level-funded arrangements can price based on your actual group's health profile. If you have a young, healthy team, your rates reflect that reality instead of subsidizing the broader pool.

Transparency and Incentives: You see exactly where money goes—claims vs. administration vs. stop-loss premium. This visibility lets you make informed decisions about plan design, wellness programs, and cost containment. You're no longer just writing checks into a black box.

Brokers report typical savings of 15-30% compared to fully-insured renewals. For a startup spending $100K+ on health insurance, that's real money.

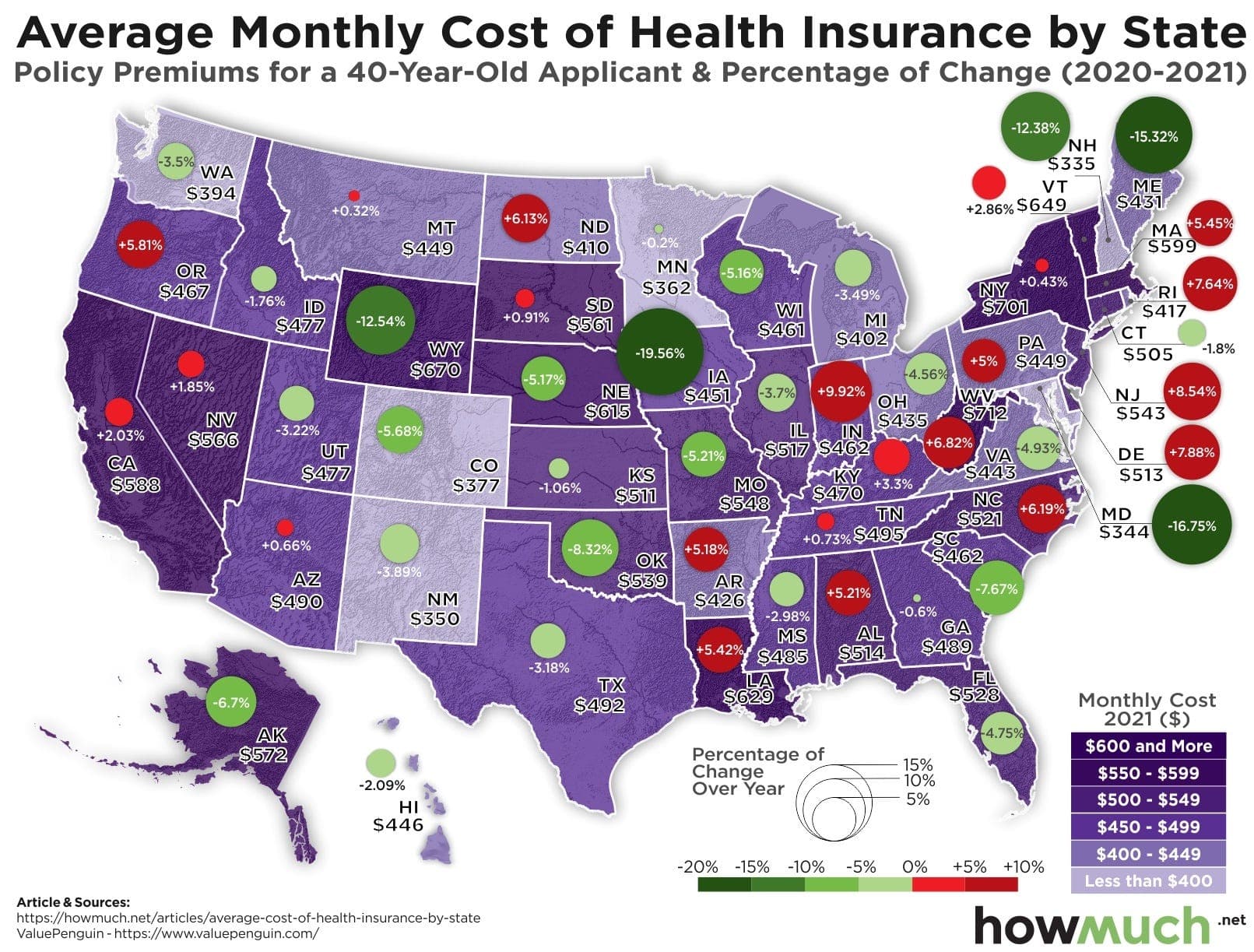

The National Picture

Level-funded plans have exploded in popularity over the past decade. In states with permissive regulations—Texas, Ohio, Florida, and most of the country—small businesses have embraced them as an escape valve from ACA market costs.

The structure works. Claims data shows that level-funded groups maintain coverage, access the same provider networks, and achieve meaningful cost reductions. It's not "junk insurance"—it's the same self-funding strategy that large employers have used for decades, adapted for smaller scale.

Why You Can't Do This in New York or California

If level funding is so effective, why isn't every startup using it?

Because in New York and California, regulators have made it effectively illegal for small businesses.

The mechanism is subtle but powerful. Under federal law (ERISA), states cannot regulate self-funded health plans directly—that's federal jurisdiction. But states can regulate insurance products sold within their borders, including stop-loss policies.

So these states weaponized stop-loss regulation to block level funding.

New York: The Outright Ban

New York Insurance Law (Sections 3231 and 4317) prohibits the sale of stop-loss insurance to any employer with fewer than 100 employees. Full stop.

No stop-loss means no level funding. Without that financial backstop, a single catastrophic claim could bankrupt a small company. The state didn't ban self-insurance (they can't under ERISA)—they just made it economically suicidal.

The policy rationale, articulated by the Department of Financial Services, is explicit: prevent "adverse selection" that would destabilize the community-rated small group market. If healthy groups exit the pool, premiums rise for everyone remaining, potentially triggering a "death spiral."

California: The $40,000 Toll Booth

California took a different approach with Senate Bill 161 (2013), championed by State Senator Ed Hernandez.

Instead of banning stop-loss outright, California set the minimum "attachment point" at $40,000 per individual. This means if you self-insure, you're responsible for the first $40,000 of claims for each employee before stop-loss kicks in.

For a 10-person company, that's $400,000 in potential exposure before your insurance activates. For most small businesses, that's unacceptable risk. The high attachment point functions as a de facto ban—not by prohibition, but by making the economics impossible.

In Texas, by contrast, you can get stop-loss with a $10,000 or even $5,000 attachment point. The risk is manageable. The option is real.

The Philosophical Divide

The defenders of these restrictions make a coherent moral argument: health insurance should be a vehicle for social solidarity. The healthy subsidizing the sick isn't a bug—it's the point. If you allow risk segmentation, you abandon the most vulnerable to unaffordable coverage.

But this solidarity is selectively enforced.

Large corporations self-insure freely under ERISA, exempt from state mandates and community rating. Amazon doesn't subsidize the New York small group pool. Neither does Goldman Sachs or Google.

The policy creates two classes: enterprises large enough to escape the regulated market, and small businesses trapped inside it. The bodega subsidizes Walmart's healthcare savings.

The Results Are In: Restriction Hasn't Worked

If the goal of these policies was to stabilize the small group market and protect consumers, the evidence suggests failure.

New York's Shrinking Pool

From 2020 to 2024, the number of covered lives in New York's small group market dropped by 24%, from 960,000 to under 740,000. Businesses aren't staying in the pool and paying high premiums. They're dropping coverage entirely or finding other workarounds.

The "death spiral" that regulators feared from adverse selection is happening anyway—just driven by unaffordability rather than segmentation.

Premium Explosion

New York premiums have increased dramatically despite—or perhaps because of—the restrictions:

- Rochester area: +45% over four years

- NYC and Long Island: +36-38% in the same period

California's small group premiums have grown at 7% annually since 2022, outpacing national averages.

The Comparative Data

An Urban Institute analysis found "New York's average lowest gold premium was nearly double that of states with competitive markets." The "protection" of the risk pool hasn't translated to affordable coverage. It has created some of the most expensive small group insurance in the country.

Meanwhile, in deregulated states, level-funded plans are saving small businesses 15-30% while maintaining coverage. The market that regulators feared would collapse is functioning.

The Federal Fix: What's Actually Moving in Congress

There's reason for cautious optimism. The Self-Insurance Protection Act (H.R. 2813 / H.R. 2571) is working through Congress with bipartisan support.

The bill would amend ERISA, the Public Health Service Act, and the Internal Revenue Code to explicitly exclude stop-loss insurance from the definition of "health insurance coverage." This technical change would have massive practical implications:

It would preempt state laws like California's SB 161 and New York's stop-loss ban.

By establishing a federal definition that separates stop-loss from health insurance, the bill would strip states of their authority to set prohibitive attachment points or ban the product for small employers.

The bill has been reported out of the House Committee on Education and the Workforce. It faces opposition from the NAIC (the state insurance regulators' association) and some Democratic leadership, who argue it would destabilize state markets.

But the affordability crisis is creating strange bedfellows. Small business associations spanning the political spectrum are unified in support. The Chamber of Commerce and NFIB are aligned. Even some traditionally ACA-supportive groups are acknowledging that current policy isn't working for small employers.

What This Means for Founders

If you're running a startup in New York or California, you're currently trapped. Your options are:

- Pay the community-rated tax: Accept that your healthy team subsidizes the broader pool, budget accordingly, and treat it as a cost of doing business in these states.

- Use ICHRA: Shift the administrative burden to employees and access the individual market. Doesn't solve the cost problem, but provides flexibility for distributed teams.

- Relocate key functions: Some companies incorporate entities in permissive states to access level funding for portions of their workforce. This is complex and may not be worth it at small scale.

- Wait and advocate: The federal legislation could change the landscape within 1-2 years. If the Self-Insurance Protection Act passes, level funding becomes available nationwide regardless of state restrictions.

In the meantime, understand what you're paying for and why. The $1,200/month premium for your 26-year-old engineer isn't actuarial reality. It's policy choice. A choice made by regulators who decided that small businesses should bear the cost of social solidarity while large enterprises opt out.

That's worth questioning.

Get Better Health Insurance for Your Startup

Rivendell helps startups navigate the complex health insurance landscape. Whether you're exploring level-funded options, ICHRAs, or traditional group coverage, we'll help you find the most cost-effective solution for your team.

Get a Quote